Death of the Rev. Dr. Amasa Converse – 9 December 1872

.

.

[Editor’s Note: The following are The Christian Observer obituaries for publisher the Rev. Dr. Amasa Converse from the 11 and 18 December 1872 issues, which provide a detailed history of the publisher and much about the Presbyterian church and the culture of 19th century America. Many thanks to Wayne Sparkman, Th.M., C.A., Director, PCA Historical Center, for providing this information.]

.

The Christian Observer 51.50 (11 December 1872): 1, column 1.

DEATH.

The Senior Editor of this paper died on Monday morning at ten o’clock.

He had passed the three score and ten years allotted by the psalmist to man. His old age was green and vigorous, and abundantly filled with labors for the good of the Church. The present number of the paper contains several pieces from his pen. He worked continuously till within a few days of his death, from eight to ten hours a day. He was preeminently a worker. Of him it may be said with peculiar force, that he “hath done what he could.”

His last labor was to write to an absent son. After finishing his letter on Thursday night of last week, he himself took it to the post office, not two squares away, that it might take the early morning train. On his return, a congestive chill was upon him. He had hardly recovered from this, when, it was found that pneumonia had invaded one lung. His frame, worn with the labors of seventy-seven years, was unable to sustain the force of this disease. He sank slowly but surely, without even a murmur of complaint or repining, and without a single groan, and died after an illness of less than four days, so calmly and peacefully that it seemed like a child dropping into sweet slumber.

And indeed, what else is it to him but a happy, blessed rest from the troubles of life? A man of much and never failing prayer, as well as unceasing labor, he has already rejoiced in the plaudit of his Lord, “Well done, good and faithful servant, enter thou into the joys of thy Lord.” His family will never forget the hour spent in his chamber every morning after breakfast, with locked door, when alone with the Lord whom he loved and trusted and served, he interceded for his family, his Church and his country. In every event he saw the hand of God. In the many troubles through which he passed, he always could recognize the good and merciful providence of God. A good man, he has received his reward.

The funeral services will be held in the Second Presbyterian Church [Louisville, Kentucky], on Thursday afternoon, at half past two o’clock.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

The Christian Observer, 51.51 (18 December 1872): 1.1-5.

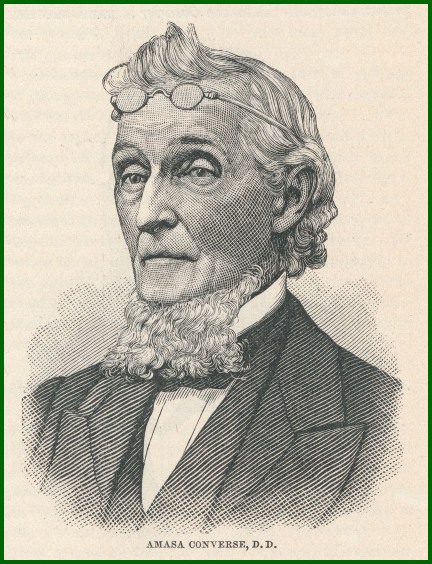

THE REV. A. CONVERSE, D.D.

For nearly half a century this venerable servant of Christ has been known and honored and loved in the Presbyterian Church. His influence has been felt in thousands of families, as from week to week, during nearly the whole of this period, he has visited them through the press—cheering, encouraging, instructing them, and exerting a decided influence in molding their characters and lives. In not a few families his paper has been taken by parents, children and grandchildren. In many households two generations have learned their letters from his paper, and grown up under its instructions. His position as probably the oldest editor, at the time of his death, in the United States, and one of the ablest; his extensive influence, and his exalted worth, demand a more extended notice than was given your readers last week. There are many among them who want to know more of this great and good man, whom, though they never had seen, they had learned to love and reverence—than is contained in your brief notice of his death. I have, therefore, ventured to note down a few facts respecting his life and services, and will thank you, Messrs. Editors, to correct any inaccuracies as to dates, &c., before giving them to your readers.

His Boyhood.

Our venerated Father in the ministry first saw the light amid the sterile hills of New Hampshire, on the 21st day of August, 1795. He was the son of pious, God-fearing parents, who continually bore the spiritual interests of their ten children upon their hearts, and daily remembered them in their prayers to God in the worship of the family. From them he inherited that robust vitality of constitution and those powers of endurance which enabled him in after years, though in feeble health, to bear up under a multitude of labors, that most men in vigorous health could not have performed; from them he inherited that fortitude and cheerful courage which he possessed in so remarkable a degree; and that indomitable will and firmness of purpose which were so essential in the trials and struggles through which, in the Providence of God, he was called to pass. Of this world’s goods they had not a great deal to give him. But they gave him what was a great deal better—habits of industry, and such training as only godly parents, gifted with good, strong, practical common sense, can give the children of their love.

A fondness for books developed itself at an early age, and he made the best use possible of the limited opportunities of instruction that were afforded in that backwoods region, at a time when the growling of the bear and the howling of the wolf had not entirely ceased to be heard in the surrounding forests. As soon as he was old enough to work—say at the age of six or seven years—he went with his father and brothers to the field, and for twelve or thirteen years, until almost grown, he was actively employed in the labors of the farm, with the exception of the school opportunities afforded for a few months in the winter. A little incident which occurred when he was ten or eleven years old, doubtless exerted an influence on his subsequent life. Fifty copies of the weekly paper, published at Hanover, N. H., were taken in his native township. To save postage—in those days no small item—the subscribers took turns in sending for the package. Child as he was, he begged his father to be permitted to go, and, mounted on horseback, he found his way alone over a hitherto untraveled road and back again, some thirty-six miles, with the bundle of papers. While here he saw for the first time Dartmouth College—here he saw the College students, whom he regarded with almost reverential awe, and he saw, too, that great mystery, a printing press, and a printing office.

From this hour his purpose was formed to pursue a college course. Only one or two young men from his community had ever enjoyed this privilege. His purpose found little favor with his associates and companions. Some of them ridiculed his aspirations. His father could not afford to send him away to school, or spare his labors from the farm. But he took hold of study with renewed energies—often rising long before day to secure time for his books before going out to work—using the odd moments which most boys waste, and bending every energy to the accumulation of knowledge. He committed the Latin Grammar to memory in ten days. One or two years before arriving of age, he proposed to his father to relinquish his patrimony [i.e., his inheritance] if he might have his time for study. By laboring with his own hands he supported himself while in school and college; and finally, after seven or eight years of unremitting efforts, masked by repeated disappointments, he was graduated with high honors in Dartmouth College, New Hampshire on the 21st day of August, 1822—the birthday anniversary, which marked the completion of his twenty-seventh year.

His Early Religious Impressions.

It was while he was at Phillip’s Academy in Andover, Mass. while fitting for College, that he made a profession of religion. In a manuscript in the hands of his family, he thus describes his life and feelings at the time. He says,

“I was taught in my infancy to fear God and to offer him a child’s prayer on retiring to bed. The instructions of a pious mother were daily repeated in my early childhood, but for several years they seemed to make no permanent impression on my heart, which was alienated from God from my infancy. The exhortations of my father, and the hallowed lessons of piety received from both parents, seemed to be lost on me. I soon neglected the habit of prayer, and indulged the hope of an infidel that the sanctions and doctrines of the Christian faith were a fiction. Yet I cannot say that the parental piety and example were wholly without influence on me.

I recollect that in one instance, my father, when sick, fainted and fell to the floor, while praying with his family. I feared that he was soon to die, and retired to a secret place to offer prayer that God would spare his life. His health was restored, and the impression made by this incident was soon effaced or disregarded.

I was required to read the Scriptures, and also to commit the Westminster Shorter Catechism to memory. But I felt little or no interest in what I read in the Bible, and my lessons in the Catechism were an irksome task. Both were neglected and discarded before I was sixteen years old, and I was captivated and led into known sin by associates addicted to profane swearing, card playing, Sabbath breaking, promiscuous dancing parties, and other follies of thoughtless youth. Such were the vain pursuits in which I spent time, and sought for pleasure, idly dreaming that sensual gratification could render me happy. Thus much of my time was spent in youthful amusements and follies, which rendered me deaf to religious instruction and the claims of the gospel to my heart. By these amusements I was hardened in the practice of known sins, in which I indulged with little or no restraints, except such as a regard for reputation among my friends imposed on me. Thus I lived for seven or eight years, till I reached the age of nineteen.

In the winter of 1815 or ’16, I became acquainted with Mr. Asa Lord, a plain man of superior understanding, whose Christian life commended religion to my attention more impressively than anything I had ever heard from the pulpit. It suggested inquiry, and inquiry led me to see that I was living like an atheist, without God and without hope in the world. I began to pray, and continued in the practice for weeks and months. The more I prayed, the more impressively was I convinced that I was a poor, miserable sinner, alienated from God. I desired to know what the happiness was of which I had heard religious people speak. I knew nothing of it. My religious views made me miserable. I sought for information in the religious experience of others. I knew not the way of salvation; I was in the dark. In this state of feelings I continued for years, trying to pray daily, but apparently making no progress. At times I was tempted to think that God was a hard, unfeeling tyrant, that he had given me a sinful nature, and then required me to change it, which I could not do. I was tempted to reject the doctrines which affirm the foreknowledge and sovereignty of God.

Such was the state of my mind when I resumed my studies in Phillips’ Academy in 1816. At one time tempted to renounce all belief in the doctrines of religion, and at another, almost amazed that God did not instantly sink me in hell, I sought retirement and offered my imploring prayer for mercy; but know not whether that prayer was then answered. I was gloomy; my religion, if I had any, gave me no conscious hope in the grace and love of God. Thus I continued for twelve months or more, thinking if I was rejected as a reprobate, I would perish, pleading for mercy.

One evening my fellow-students thinking probably that I was truly a Christian, were looking for me to conduct our weekly prayer meeting, which was numerously attended; but I was not found till the services were commenced, and then was in the meeting, in the corner of a large schoolroom, enjoying such a view of God, of his majesty and love as I had never had. I felt that if I were in hell, I would adore him and bless his name for his supreme excellence and glory. His perfections seemed inexpressibly lovely and glorious. The vision lasted perhaps an hour. I had then no hope that I was a converted man, or that my heart was changed. My ecstatic feelings were but for an hour or two, and then gradually subsided into the former state of doubt in regard to my spiritual state. But from that period, I began to examine my feelings. I resolved to be a Christian—a resolution I had previously formed—though the world were in arms against me. I began to think that I loved God just as He was revealed in his Word; that I took delight in his service, and that I would preach his gospel, if not prevented by some insuperable obstacle.

After a few weeks, I had a conference with [the] Rev. Drs. Porter and Woods, and was received as a member of the Congregational church connected with the Theological Seminary in Andover.”

His Early Ministerial Life.

In Princeton Theological Seminary he enjoyed the counsels and instructions of those three giants of Presbyterianism—the Rev. Drs. Archibald Alexander, Samuel Miller, and Charles Hodge. But while pursuing his studies here, severe illness brought him to the borders of the grave. He had become so much wasted by disease that Dr. Alexander, who took the same interest in him as if he were an own son, and who had shown him every kindness during his protracted illness, advised him to seek a warmer climate, and engage in such ministerial labors as would keep him much of his time in the open air, and give a good deal of exercise on horseback.

Hence, his removal to Virginia on December, 1824. His home was in the family of the late Dr. Wm. J. Dupuy, of Nottoway county, and his missionary field embraced large portions of Nottoway and Amelia counties. While laboring here, he was supported in part by the Young Mens Missionary Society of Richmond. And it was while engaged here that he was ordained to the full work of the Gospel Ministry by Hanover Presbytery, in April, 1826. The Rev. Wm. J. Armstrong, D.D., preached the sermon, and Rev. Benjamin H. Rice, D.D., delivered the charge to the newly ordained evangelist. In those days and in that region it required great moral courage for a man to make a profession of religion. Infidelity was popular; religion was regarded not merely with indifference, but with positive aversion. Yet his labors here were acknowledged by the Lord of the Vineyard, and the churches strengthened by the accession of valuable members.

His Editorial Life.

His long and eventful editorial career commenced about the 20th of February, 1827. The Family Visitor had been started in Richmond, Va., in 1822, at the instance of the Rev. John Holt Rice, D.D. He was urged by Dr. Rice, towards the close of the year 1826, to take the editorial charge of that paper, and of the Evangelical and Literary Magazine. After prayerful consideration, he decided that with a weak voice and impaired health, he could perhaps do more good with his pen than with his voice; and from that time until his death, a period that lacked only about two months of completing forty-six years, he has been uninterruptedly at the head of the same journal.

Trials and discouragements greeted him on his first entrance upon editorial life. The circulation of the paper was inadequate to make it self-sustaining. Its proprietor failing, he found himself burdened with pecuniary liabilities. The skies looked indeed dark. If he could at that time honorably have relinquished editorial labors, he would probably have done so. If I mistake not, he cherished a purpose to withdraw from the press as soon as he should have paid off the debts which it owed. When the paper came entirely into his possession, he made his appeal to the churches. It was nobly responded to. The circulation of the Southern Religious Telegraph (for this was the name it now bore,) was more than doubled; and for a season his position was a pleasant one.

But dark clouds were beginning to gather on the ecclesiastical horizon. The strifes in the Presbyterian Church, which culminated in the division of 1837-38, were becoming more and more bitter. As long as it was possible to be neutral, his great aim was to pour oil on the troubled waters. When it became necessary to take a decided stand with one party or the other, his convictions of right, and not his pecuniary interests, decided him in his course. And he took the stand he did, with the full knowledge that it was not the popular side in the part of the Church in which he labored, and that it would probably cost him a large part of his subscription list. In this he was not mistaken. The heavy losses which were sustained at this time, led him to regard with favor overtures for his removal to Philadelphia, and the union of the Philadelphia Observer with the journal under his care, which was effected in January, 1839. Since that date the paper has been known as the CHRISTIAN OBSERVER.

His energy and promptness were exhibited in 1854, when the office was destroyed by fire at night. The loss was a heavy one. But its editor was equal to the emergency, and the issue of the next number was not delayed a single hour by the fire.

Even before this time many in the Synod of Pennsylvania had become dissatisfied with the paper, because it so steadily frowned upon that abolition sentiment which was destined, in a few years, to deluge our land with blood. The opposition to Dr. Converse, from this source, became stronger and stronger; and that politico-religious spirit which is the bane of the Northern Church, became so fierce that Dr. Converse stood almost alone in the Synod of Pennsylvania, in opposition to it. An association was formed to buy him out, if possible, and if not, to establish another paper, which would in this matter, pander to the views of those by whom he was surrounded. He knew that if he refused the offers made him, another paper would be started with large capital, backed by powerful personal influence, with which it was doubtful whether he could successfully compete. But he had in his hands a powerful engine for the “diffusion of truth,” and no earthly consideration could move him to surrender it into the hands of others, who he believed would use it for the dissemination of error. The American Presbyterian was, therefore, started in 1856, in opposition to the CHRISTIAN OBSERVER. Large sums of money were expended upon it. But the veteran editor manfully and successfully stood his ground. And when the war burst upon the country, intimidation could not move him, threats of mob violence could not disturb him. In the Lord’s hand he felt safe as long as the Lord had a work for him to do. And he continued his labors in Philadelphia for the purity of the Church and the peace of the country, until the strong arm of the military power was invoked against him. On August 22, 1861, Mr. Seward “rang his little bell.” Dr. Converse was visited by the United States Marshal, his paper suppressed, his property seized, and almost the entire savings of a lifetime destroyed.*

[*It is stated that Marshal Millward, who was charged with the arrest, told a friend that he had orders in his pocket to take Dr. Converse into custody, and though he knew he was liable to severe reprimand for failing to obey instructions, a strange and unaccountable feeling came over him in the presence of the venerable servant of Christ, which prevented his carrying out that part of his orders.]

By the middle of September—less than a month after his paper had been suppressed in Philadelphia—he had run the blockade, and the CHRISTIAN OBSERVER had reappeared in Richmond, Va. His labors there during the war, through the press and among the soldiers are well known. His venerable form, as it appeared in our hospitals waiting upon the wounded, conversing and praying with the sick and dying, and preaching in the hospitals and prisons of Richmond, will long be remembered by thousands, not only of the Confederate soldiers, but the Federal prisoners..

With the close of the war came another great reverse. In common with thousands of others, nearly every earthly possession he had, had been swept away, and at three score and ten he had to recommence the battle of life with scarcely more of this world’s goods than he possessed when he left college forty-four years before. His printing office, providentially, was spared when Richmond was burned; and undaunted by the difficulties ahead, without a sufficient amount of available means to meet the current expense of the office for a single week, before mail routes were reopened, or post offices established, or money was in circulation, before any other weekly paper in the Southern States dreamed of resuming publication, he launched the CHRISTIAN OBSERVER anew upon the sea of journalism. He evidently felt then, as he did on his dying bed, that with God for a friend, he would not want. And, if I am correctly advised, its voyage since then has been a prosperous one. His last days were his best days. He had a larger circle of friends and was wielding a wider influence than at any previous period in his life as a journalist.

The Close of Useful Life.

Our tale is almost told; but a few sad lines remain to be written. A wish that the editor had often expressed was about to be gratified—he was to die with his harness on—to “wear out instead of rusting out,” as he expressed it. He had been very much weakened by indisposition for a few days, but on Thursday, December 6, he was as usual attending to his regular labors. At night he went to the post office to mail a letter to an absent son. He returned in a few moments with a heavy chill upon him. After holding family prayers with his wife, as had been his custom through life, he retired to his bed, from which he never rose. Pneumonia claimed him as its victim. For three days he rested quietly, almost unconsciously most of the time, and on Monday morning, December 9, at 10 o’clock, he entered into that rest that remaineth for the people of God. A look of pleased surprise settled on his countenance, as though the veil had been removed at the moment of death. His last words were the appropriation to himself of the precious promise in the twenty-third Psalm, “I shall not want.”

Characteristics.

No sketch of the life of Dr. Converse would be complete, which failed briefly to call attention to some of his leading traits of character. No analysis of character will be here attempted, but only a few salient points hastily touched upon.

1. He was eminently a man of prayer. In his busiest days he had his hour for private devotion, and his children well knew that at that time “father’s room” was a sacred spot, on which they could not intrude. Morning and night he assembled his family around him with Bibles in their hands, and each in turn read a few verses, and then all united with him in earnest entreaties to the throne of grace.

2. His firmness. Gentle and unobtrusive in his manners—not over-impetuous in disposition—living in charity as far as was possible with all men, it needed an emergency to call forth the stern purpose, which was unbending as the rocks. But when once his purpose was formed, neither fear nor favor could make any impression. Many instances of this trait, both in childhood and maturer years, could be cited, but the length of this sketch prevents their insertion.

3. Love of learning. From what has been said about his earlier years, the reader can see what he then thought about learning. Almost alone in his neighborhood he battled with obstacles that seemed overwhelming to his fellows, and instead of the life of a quiet farmer, not known beyond the limits of his own town, he has lived a life of public usefulness, and has died known, honored and beloved by tens of thousands, as an earnest and successful servant of the Cross. Having won his own education, at so much cost and pains, he early resolved that all his children should be thoroughly trained for the duties of life, even though he could give them nothing else. Faithfully this resolution was carried out. He has sent five sons and one daughter through a thorough course of study, and opened to them a wide door to influence. Most of them he prepared himself for college, hearing their recitations in the morning before entering on the arduous labors of the day.

4. His life as a preacher. As a preacher Dr. Converse was comparatively unknown to the Church at large. A feeble frame, weak voice and natural diffidence early admonished him that his work was not in the pulpit but at the desk; and for half a century, lacking four years and two months, the pen has been the weapon with which he has battled vigorously for the church. Still his voice has frequently been heard in the pulpit, taking the place of some absent brother, and his sermons have been blessed to the good of immortal souls.

Many other points of character might be noticed, but I must draw this sketch, already extended beyond my intention, to a close. The widow of our beloved friend and six of their eight children survive him. Of the five sons, three are ministers of the gospel. Two of them are connected with the OBSERVER, and the third is a pastor in Virginia. That they may follow the footsteps of their sainted father is the hearty prayer of their friend, who deeply sympathizes with them in the heavy loss which they, in common with the whole Church, have sustained in his death.

.

Comments are closed for this Article !