William Morrison – The Experience of God’s Faithfulness

By Paul Carter – Pastor, Grace Presbyterian Church (PCA) – Lexington, Virginia

Introduction

On the campus of Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, there is a marker honoring William Morrison, missionary to the Belgian Congo. The marker is located on the right side wall at the front of Lee Chapel on the opposite side from where former C.S.A. General Robert E. Lee sat during daily chapel services.

There is another honoring Morrison alongside the ruins of Monmouth Church about 3 miles west of Lexington on U.S. Route 60. These markers were placed because William McCutchan Morrison grew to become a world renowned figure. Through widespread correspondence, his speeches before both the British Parliament and the U.S. Congress, and finally by an internationally reported trial based on false charges against him and his fellow missionary William Shephard, he brought the pressure of the world to bear against King Leopold III of Belgium in order to protect the his beloved Congolese people from the abuses of the Belgian-government controlled Kasai Trading Company. Morrison’s motivation to protect the Congolese stemmed from his understanding his calling as a minister of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Therefore, Morrison’s life is an example of one who was faithful under pressure because he lived his based on the faithfulness of God to His Covenant people.

I. The Making of the Man

In the Providence of God, Morrison’s great-great grandfather emigrated from Scotland to Ireland in about 1750 for that freedom to worship as Scripture and conscience led him to worship. Leaving a successful business in Ireland, he settled in Philadelphia. Nothing is reported of him or the family except that one son, Morrison’s great-grandfather, was a teacher who married a German woman who, remarkable for that day, had been educated at the University of Heidelberg.

.

.

As remarkable is that Morrison’s great-grandmother’s extended family contained several teachers and her immediate family included five Presbyterian preachers; both sets of characteristics joined themselves in Morrison himself. His great-grandparents moved first to Staunton, Virginia and then on to Lexington, Virginia, where they raised their family. Morrison’s grandfather, Robert, was the youngest child in his family and grew up to be an elder in the Monmouth Presbyterian Church. Robert Morrison was called “the right arm of the church,” and “a power for righteousness in the community.” Robert Morrison had three sons; the oldest named Luther who inherited the family farm and also became an elder at Monmouth Presbyterian Church.

Luther married a deeply spiritual woman from Bath County, Virginia, who was soon to become known as a wise spiritual and ministry counselor to her pastor and many others in the community. William Morrison, the first of eight children of Luther Morrison, was born on November 10, 1867. In addition to the past family emphasis on education and service in the Church of Jesus, William had three first cousins who were missionaries in China. As was considered normal in his family, William’s parents and his family offered him to the Lord for service in the gospel ministry at his birth. Therefore, his upbringing was considered to be training for the ministry from his earliest days, should God in His mercy grant such a calling. William’s aunt Susan Crawford, also known for her love for Christ and for her spiritual maturity, providentially, lived with the family having a significant role in William’s early spiritual development.

Signs of his later gifts and leadership began to be seen when William attended a small high school and organized a debate club and a singing class. At the age of sixteen, William began attending Washington and Lee University and there decided that he wanted to become a lawyer. At Washington and Lee University, William was a good student, full of common sense, who told the truth, and who was faithful to do what he said he would do. He also won honors as a debater. William was respected because of his character and his abilities but no one in Lexington at that time would have guessed his future as a missionary and a human rights advocate in Africa.

As a young man, William had no interest in going to Africa. At age nineteen, a year before he graduated from college, William had not yet professed faith in Jesus Christ. He had no intention of being a missionary. The practice of law was to be his future. He would not surrender to Jesus, because that meant that he must preach, and as Morrison said, “for me to preach is for me to be a missionary, and I don’t want to be a missionary.”

William Morrison’s father passed away before William finished college, but unbeknownst then to William, the providence of God was hard at work in his life. When Luther Morrison was on his deathbed, he was asked what he was going to do about William since he had been consecrated to the ministry and he wasn’t even a Christian. Luther Morrison said “I consecrated William to God, and have never taken him back, and in God’s own good time all will be well.” However, Luther Morrison died before he saw William’s consecration to the ministry come to fruition.

But God was faithful and in His mercy granted the prayers of a father, mother, and many family members. William Morrison surrendered to Jesus Christ soon after the death of his father. He finished college at age twenty but could not attend law school for financial reasons. So William became a school teacher in Arkansas, interestingly, as a means to stay out of the ministry. As Jesus gradually changed William’s heart, and through no particular experience or great crisis, he came to believe that he was fighting against God, and then entered Louisville Seminary in Kentucky. Just before William’s graduation from seminary, he read an article written by a missionary serving in Africa describing the needs and opportunities there. God used that article to begin to turn toward him to missions as the field in which he was to serve Christ. When Morrison announced his decision at the church he worshiped in during his seminary studies, a Sunday school teacher said that she had read the same article as had William, and it meant so much to her that she read it to her class of little girls, and they all began to pray together that Morrison would answer God’s call.

By the providence of our faithful God, the young man who was going to be anything but a missionary, wrote in his diary on his last visit to Lexington, Virginia before going to Africa:

“This day I leave home and mother, brothers and sisters, and many hallowed memories of home and native land, and go far hence to gentiles in obedience to the command of my Master. This desire came to me, through the peculiar dispensation of God’s providence, about eighteen months ago. I have every reason to believe it was in answer to the prayers of some little children in Louisville, Kentucky. As I enter this great and trying work, my prayer is “O God, I beseech thee to give me an abundant outpouring of the Holy Spirit, making my own life an open Gospel, an epistle known and read of all men. O God, pour out Thy Spirit upon Darkest Africa, and may the long night be broken, and may the brightness of the Sun of Righteousness soon illuminate that benighted land.”

Lessons

1) A person’s background and training are used of God to mold his servants.

2) God uses our experiences and interests to train us for our future service to His Kingdom.

3) God is faithful to prayers of fathers, mothers, aunts, and even little girls in Sunday School.

4) Who are you praying for, helping to train, raising up, or working to see Christ developed in? It is never too late to start.

II. Africa

At William Morrison’s birth, missionaries to Africa were still packing their clothes to be sent to their ministry site in coffins because so many of the missionaries died within the first few months. When Morrison arrived in the Congo, there were eight missionaries, one Sunday School class, one day school, and four small missionary huts of mud and sticks. Morrison wrote “pretty close quarters, but more than my Master had.”

Morrison’s first missionary success was when a war broke out between two tribes closing down the trade routes and so causing immense hardship on the people. It also caught Morrison away from his home in the Congo. When the conflict quieted, against the advice of others, Morrison started home. But on the way he decided that he would attempt to call the tribes together and try to make peace. Amazingly, almost unbelievably, Morrison succeeded in making peace between the tribes. Because of his boldness in stepping out as a peacemaker, he was given an African name which meant: “Keep the paths open.” This action also opened new doors for ministry. Now being sufficiently trusted by the Congolese, peacekeeping became a significant part of Morrison’s ministry throughout the rest of his missionary service. More in keeping with what we think of as more traditional missionary work, Morrison began to work to translate the Bible into the Bakuba language. Morrison’s translation work brought him into contact with many other Congolese to whom he taught the Gospel, and in so doing, Morrison obtained deeper insight into the Congolese character, culture, and ways of thinking. His work was still being utilized into the 1960’s.

Morrison’s work was often discouraging. He once wrote in his diary: “I am almost oppressed with discouragement when I think of Bible translation. Three great monsters rise before me in the darkness: first of all, my work is with the very bottom of humanity – perhaps as low as the lowest, with an unbroken history of perhaps thousands of years of ignorance, superstition and spiritual darkness. Another difficulty is the fact that all the customs, manners, pursuits and minds of the people are so different from the people described in Bible history. The worst of it is that these people can form no conception of these strange customs and circumstances. But perhaps the greatest obstacle of all and the most discouraging is the fact that after I have spent many weary years in translation work, not one man can read a word of what I have written…I have not seen a single character that seems to indicate the most remote conception of a written language.” To Morrison’s ministry, then, was added teaching, one of the pursuits he had earlier used to run from God and His calling.

Another, Morrison’s debating skills which he thought would propel him into a career as a lawyer, were used in mediating disagreements, and were soon to be used in disputes with the government. After obtaining a good foothold for the Gospel through the development of schools and churches, and after personally spending several months of work developing friendships and ministry with various government and Kasai Company officials, Morrison’s mission received notice that it was being closed by the government. The ministry was given fifteen days to move. Morrison wrote a letter in protest but to no immediate effect. It was this incident that started what was to become twenty years of continual battle between Morrison and the government of the Belgian Congo.

Lessons

1) God doesn’t waste training.

2) Even when one can’t see why, when it doesn’t seem useful, or the training seems destined to be used in opposition to God’s call, God is behind it. (Romans 8:28)

III. Fighting the Government

William Morrison’s mission recovered from the forced relocation, and began to grow significantly when the chief of the largest Congolese tribe, the Bakuba, asked William Morrison and William Shepherd, an African-American missionary colleague who preceded Morrison to the Congo by two years, asked advice on how to deal with the Belgian governors of the Congo. Morrison’s and Shepherd’s audience with the tribal chief was significant, because no missionary had previously been allowed to come to his village or to see the chief. Some of the chief’s own people had never seen his face.

The cause of this breakthrough was that the chief was being hard pressed by the government for his refusal to deal with foreigners and so he was scared that the government would do to him and his people what they had done to the cannibalistic tribe called Zappo Zaps. When the cannibals would not cooperate with the Kasai Company, government troops attacked them. Morrison had protested the military attack on the Zappo Zaps and so was seen as a champion for them and the Congolese in general. Morrison’s and Shepherd’s meeting with the Baluba opened additional doors of trust and an even greater opportunity to advocate for the people he had gone to Africa to serve.

A few months after Morrison and Shepherd met with the Baluba chief, Morrison left the Congo for a one year furlough. Before coming back to the States, he was first sent by his mission to Belgium to speak to the government on behalf of the mission and the Congolese people. The Belgian response to his requests for fairness and justice was public vilification.

Seeing that Leopold III would not honor his treaty obligations to “seek the moral and material regeneration of the Congo natives,” Morrison decided that it was time to go public with details of the Belgian abuse of the Congolese people. Morrison spoke about the Congo situation all across the United States. He then went to Washington DC and spoke to several high ranking U.S. government officials, including Theodore Roosevelt’s Secretary of State, Elihu Root. Additionally, Morrison had several conversations and correspondences concerning the Congo with Mark Twain, who, though no friend to the Faith, wrote a popular work against Leopold III. Morrison also spoke to high level government officials in England and to the British Parliament.

The result was that Leopold III began receiving international pressure to right the wrongs of his government in the Congo and to uphold his treaty promises to “watch over and care for the native tribes.” The charges against Leopold III included grossly unfair labor taxes, appropriation of land and the resultant effective imprisonment of the Congolese natives, abuse of the Congolese by Kasai Company officials, binding children to long-term contracts they did not understand, injustice to the Congolese in the courts, and sending punitive expeditions against the Congolese in order to extract taxes. These charges had also been made by the commission previously appointed by the Belgian Government itself but were never stopped.

While Morrison was at home in the United States, he also found time to meet and marry his wife, a courageous woman of God who was to play a hard role in the coming events. Immediately following the wedding they began the planning to go back to the Congo knowing that he was now a target of the Belgian Government and that circumstances were likely to be much more difficult for the two of them and so for their ministry. Upon arriving in the Congo, he found that the problems of Belgian abuse of the Congolese had worsened in response to Morrison’s global efforts and that steps had been taken to keep them better hidden from the rest of the world. Congolese people were now afraid to say anything for fear of their lives.

In response to the increasing abuses, William Shepherd wrote an article for the mission’s “prayer letter” outlining the problems of the Belgians stealing rubber from the Congolese, using their women for their pleasure and as slaves, taking their food and their copper, etc., and then torturing them to extract more. The prayer letter reported additional details of the Belgians’ cutting off the limbs of Congolese natives and killing them. The Kasai Company response was to say that Shepherd was mistaken and should not have listened to the lazy and lying Congolese. Shepherd offered to prove the claims against the Belgians in court. William Morrison, as editor for the prayer letter, was blamed for the publication of the “mistakes.” He gladly accepted the responsibility.

As it is in modern-day America, problems are just problems until they adversely affect the stockholders’ money. The Kasai Company stock fell because of Morrison and Shepherd’s work. Also as in modern-day America, a lawsuit was filed against them; this one focus on the charge of libel because of the publication of the actions against the Congolese.

There was no question in Morrison’s mind of the trial’s outcome because the courts were set up by the Belgian government who controlled the Kasai Company. The Belgian’s had successfully sued and deported a British missionary who tried to showcase the abuses. The British missionary arrived at the trial with several Congolese witnesses ready to prove his case. The witnesses were immediately arrested and, without them, the British missionary lost his case. He was assessed a fine, his reputation and ministry were destroyed, and the cause of the Congolese and Christ’s Church was greatly harmed. The British government appealed and won the appeal but the reversal was never publicized. So the Kasai Company went on as before free to carry out their abuse of the Congolese.

The same sort of treatment given to Morrison and Shepherd was apparent from the start. The court date was set for May 25, 1909, just a few weeks from the time the suit was filed. The trial was to be held in Leopoldville, 1000 miles from where Morrison and Shepherd were living. The dry season had arrived, which meant that Morrison and Shepherd would find it impossible to travel downriver to Leopoldville. And there were no roads through the jungles in those days. Also, Morrison’s and Shepherd’s witnesses were members of the Bakuba tribe; a people who rarely consented to travel outside of their home area. As expected, the court was ordered to proceed without the Bakuba if they did not arrive in time. Nothing was mentioned of the fact that the allegations of the missionaries were first alleged by the Belgian government’s own commission on the Congo. In light of those circumstances, Morrison and Shepherd understood clearly that this trial was purely an attempt to silence them by setting up the court so that they would lose, as had the British missionary, and thus shaming them and their ministry before the world.

An additional problem developed. No lawyer who could practice in a Belgian court would take Morrison’s and Shepherd’s case. When the date arrived for Shepherd and Morrison to be in court, the missionaries had no lawyer nor had they been able to get to the court in order to get a court-appointed defense counsel. The American Consul ended up representing Morrison and Shepherd at this first trial and began by asking for a continuance. It the first of many surprising moves made by the Kasai Company, they agreed with the motion. It turned out that the Kasai Company lawyer had been unable to get to Leopoldville, also.

July 30, 1909 was set as the new court date, but it was then moved again to September 20th. Regarding Shepherd’s and Morrison’s finding a lawyer to represent them, providentially, during Morrison’s furlough, he had befriended an Englishman named Robert Whyte, who knew a man named Jean Vandervelde, a Belgian human rights advocate and member of the Belgian Parliament. The Kasai atrocities were exactly the kind of concerns Vandervelde held about his own government. Therefore, he was happy to take the Shepherd and Morrison case and began and investigate the situation himself. The Kasai Company lawyers unsuccessfully moved to drop the case at that point because Vandervelde’s representation of Shepherd and Morrison changed everything for them.

The Kasai Company’s suit against Morrison and Shepherd argued that:

1) Shepherd’s article was defamatory and had cost the Kasai Company a great deal of money.

2) There were no armed guards working for the Kasai Company as the prayer letter stated, though some of the guards may have owned personal guns.

3) Letters from the mission were cited stating that conditions had improved. (The Kasai Company failed to mention that the letters were over 5 years old and written before the events that caused Shepherd’s article to be written.)

4) Kasai cited letters from Morrison’s wife, thanking officials for help and inviting them to dinner. Kasai suggested that Mrs. Morrison was an immoral woman using her wiles to sway the witnesses.

5) The Roman Catholics had never complained about the Kasai Company.

Vandervelde’s defense of Morrison and Shepherd countered by showing that:

1) The Belgian Consul himself had first stated the details of the Kasai abuses of the Congolese people.

2) Judicial corruption by the local courts was widespread with ample and detail evidence of such.

3) Kasai Company papers were cited that showed that Kasai was not following their own regulations.

4) There were fifty other pending legal actions against the guards for using arms against the natives.

5) If Kasai could prove that Morrison’s and Shepherd’s intent of their writing was malicious, or that the article was proven untrue, then the court must indict its own Consul who first said the same things for the same reasons.

6) The refusal of the court to grant Morrison and Shepherd permission to call native witnesses proved that the prosecutor was morally condemned no matter what the outcome of the trial.

On October 1, 1909, William Morrison wrote a letter to a Dr. Haur in Lexington, Virginia, responding to a request for something from the Congo. The letter is difficult to read at its beginning, but further down in the body Morrison writes of the situation in the Congo saying “you may know something of how they have been crushed by the Belgians, so all their splendid work in iron and cloth was stopped for many months. Since our exposure of the situation, some relief has come, but we cannot tell how long this relief will last. The trial of Shepherd and myself for exposing this situation came off on the 20th of Sept. The judge has not yet rendered his decision, so we do not know what our fate is to be. All who heard the trial say that we thoroughly vindicated the truth of all we had said and wrote. But the judge is a tool of the government.” Morrison goes on to describe the political factors of the situation, and how if he and Shepherd were in an independent country, that they would expect justice. Morrison and Shepherd did not expect justice from this trial.

But in a postscript written on the top of that same letter and dated October 5, Morrison writes simply “Acquitted. Case may be appealed. I am threatened with new suit.” The Kasai Company and the Belgian government decided they had experienced enough embarrassment already so there were no new suits or appeals filed by The Kasai Company. Morrison went back to his village as a hero with parades in every village he passed through. Holidays were declared. Churches held services of thanksgiving. The cause of Jesus Christ advanced because, knowing the corruption of the Belgian courts as well as they did, the Congolese understood that God had accomplished the acquittal of Morrison and Shepherd.

God had been at work before the trial had ever started, knitting together relationships, raising up servants with hearts for the Congolese, even some in the Belgium government, and then used the arrogance of the powerful to bring themselves down as He had done to Pharaoh and others. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote that at the trial, Morrison stood as a more perfect and nobler representation of liberty than did Bartholdi’s statue in New York City.

Lessons

1) God blesses our faithful teaching of our children and answers our prayers for people, for events, and perhaps for far future events.

2) Isn’t it true that the Christian movement in Africa today is traced, in part, to Morrison’s aunt Susan Crawford, his mother and father’s prayers and training, his church, the prayers of little girls in Sunday School, and men and women such as Morrison, Shepherd, and their wives, who prayed and stood for Jesus Christ against all forms of unrighteousness?

IV. The End of His Life

The last letter that William Morrison wrote was concerning the treatment of the Congolese by the agents of the Kasai Company. As it turned out his protests on behalf of his flock was a lifelong battle. But it was part of the larger battle against the spiritual forces arrayed against the Kingdom of God. During his twenty short years in the Congo he oversaw an increase from two missionary “stations” or compounds to over 450 throughout the country. There were fifty converts when he arrived and over 17,000 when he died. There were no elders or church leaders at the beginning of his work but scores upon scores at his death.

In light of his accomplishments, Morrison was elected President of the Conference of Protestant Missions, an ecumenical body working together to disciple the nations of Africa. Most, if not all, of the members represented groups that Morrison had helped to begin their work in Africa. As Morrison was President, the organization met in his hometown of Luebo. He organized the conference and then led it as host and moderator. But by the end of the meeting he was not feeling well. He was diagnosed with a particularly strong strain of tropical dysentery and ordered to bed. Despite the best care he could receive, he died on March 14, 1918. At his grave, an official of the government read a paper eulogizing Morrison for his work done for the people of the Congo.

More impressive than a government eulogy were the crowds who, as followers of Jesus, rose for prayer as Morrison had taught them and prayed together that they would be submissive to the Divine Will. He was buried beside his wife in the mission cemetery.

.

Paul Carter holds the M.Div. degree from Reformed Theological Seminary in Jackson, Mississippi, the D.Min. degree from Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri, and has been the pastor of Grace Presbyterian Church in Lexington, Virginia since 1984.

.

The article William Morrison – The Experience of God’s Faithfulness was developed from a series of Sunday School lessons about the life and ministry of William Morrison.

.

All but one of the quotations and material was taken from William McCutchan Morrison: Twenty Years in Central Africa. by Rev. T.C. Vinson. Presbyterian Committee of Publication: Richmond, Virginia, 1921.

.

The remain quotation came from the letter to Dr. Haur which can be found in the Archives at Leyburn Library on the campus of Washington & Lee University.

.

The photograph of the William McCutchan Morrison memorial plaque in Lee Chapel was made possible by the stewards of Lee Chapel and Museum on the campus of Washington & Lee University, to whom we express our gratitude.

.

Memorial Texts

Lee Chapel Memorial Plaque

William McCutcheson Morrison, born November 10, 1867, graduate Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Louisv., Ky., 1892. Missionary, Luebo, Congo, Africa, May 7, 1897. Aggressive exposer of the oppression and atrocities suffered by the Belgian-Congo natives and for which he suffered prosecution, but was acquitted and vindicated. Author of the first grammar and dictionary of the native dialect, and paraphrased the Scriptures therein, D.D., W. & L. U., 1906. Married Bertha Stebbins of Nachez, Miss., June 18, 1906, who died as a missionary with him November 21, 1910. He died March 14, 1918, and was buried at Luebo.

He carried the Gospel to darkest Africa and in consecration, administration, linguistic work, practical methods and results ranks first in this field.

In happy thought of college-day fellowship, and in commemoration of his great character, his holy life-work, his heroic bravery, and his splendid accomplishment, and to keep alive in name and thought one of our greatest alumni as an inspiration to coming generations of students.

New Monmouth Church Ruins

On this spot stood New Monmouth Church. Organized 1746 by the first settlers, the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians. The first building of logs was erected in 1748 and was known as “Fork of James.” The second building of hewn timber was erected in 1767 and was known as “Halls Meeting House.” The third and last building of stone was erected in 1789 and was used until 1853. It was known as New Monmouth Church. Tablet placed by the National Society Colonial Dames of America, in the state of Virginia, under auspices of the Blue Ridge Committee.

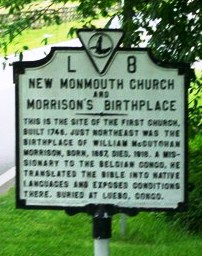

Historical Marker

New Monmouth Church and Morrison’s Birthplace

This is the site of the first church, built 1748. Just northeast was the birthplace of William McCutcheson Morrison, born, 1867, died, 1918. A missionary to the Belgian Congo, he translated the Bible into native languages and exposed conditions there. Buried at Leugo, Congo.

.

Comments are closed for this Article !