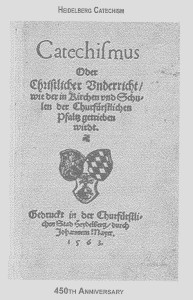

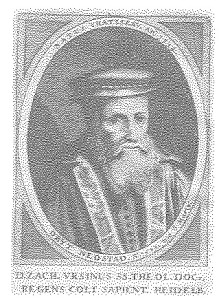

Heidelberg Catechism — 1563 — Zacharias Ursinus

.

.

By the Rev. Albert W. Kovacs – republished with permission from the Calvin Synod Herald, Vol. CXIV, January – February 2013

.

.

In the constellations above are two big bears, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, and there was a German of Breslau named Zacharias Baer who adopted the Latin form and is better known to us as Dr. Zacharias Ursinus. His fame is known to us as the author of the Heidelberg Catechism, published in 1563. In our Reformed churches throughout America, Europe and the world, we will observe its 450th Anniversary in A.D. 2013.

Ursinus, of German parentage, was born in Breslau, now in Poland. At fifteen his early studies took him to Wittenberg and the company of Martin Luther’s close associate Philipp Melanchthon, but he soon arrived in other cities to the west where he first met with Reformed scholars. When he returned to Breslau, the Lutherans challenged his views of the sacraments as too Reformed, forcing him to move and relocate in Zurich, Switzerland. There he met the noted Reformed scholars Heinrich Bullinger and Peter Martyr Vermigli.

returned to Breslau, the Lutherans challenged his views of the sacraments as too Reformed, forcing him to move and relocate in Zurich, Switzerland. There he met the noted Reformed scholars Heinrich Bullinger and Peter Martyr Vermigli.

The Elector of the Palatine, Prince Frederick II, invited him to be the professor of theology at Heidelberg, and commissioned him to write what we know today as the Heidelberg Catechism. It was written, as the Elector hoped, so that the Lutherans and the Reformed could share a common teaching tool and reduce the divisiveness in his realm. However, without delving into details here, it was not to be so. Upon Frederick’s death, Ludvig IV aligned with the staunch Lutherans and Ursinus left Heidelberg, moving to Nuestadt-on-the-Weinstrasse, where he died at only forty-eight years old. But the imprint of this big bear’s paws live on in the Reformed churches today.

Something Old — Nothing New

The genius of the Heidelberg Catechism is that it built upon the basics of most people’s familiar experiences. Whether children or adults, merely attending church services would have familiarized them with the frequently used Apostles Creed, Ten Commandments and Lord’s Prayer. Ursinus took advantage of the situation. Beginning with an evangelical preface – introducing them to God’s love for them, compelling them to see their own sinfulness which distanced themselves from God, and awakening them to Jesus’ gracious act of redemption — it took them step by step to a knowledge of how God acted to save them by his Son, Jesus the Christ.

Jesus said that he had not come to add anything to the revelation given to the patriarchs and prophets, but by his teaching and life to share the insights and godly trust that would build faith and trust in their heavenly Father. The Catechism also proposed to offer no earth shaking revelations of its own, rather to follow closely the scriptural assertions and perspectives that lead to Christian commitment and life, just as they did for the faithful apostles and disciples, and also for the members of the Church in its earliest years. Using the question and answer format, a commonly used teaching method even today, it carefully underlined each answer with several verses of the scriptures, demonstrating the validity of the answer as in accord with the biblical revelation. Although it was written fifteen hundred years after the Bible’s last book, there was nothing new in it. It was written to be trustworthy throughout the Church.

Opening its pages, the preface of twenty-two questions and answers conclude with one that asks: What is it then necessary for a Christian to believe? It leads then into the universal Church’s profession of faith, the ancient Apostles Creed. Having taught the basis essentials of Christian teachings, about the Trinity — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — and the Church, and about how that relates to the person who is saved, it immediately proceeds with the Ten Commandments to outline how a faithful follower of Jesus lives out a godly life in a personal relationship acknowledging the Almighty God, Ruler of Creation, King of heaven and earth, and also with due respect to God’s other children, be it parents, neighbors or strangers. It concludes by opening the door to the spiritual life, with an exposition of the Lord’s Prayer, taught by our Lord Jesus to the apostles, an example followed by his disciples in all ages since.

Fortunately for us, scholarship in Ursinus’ day required students under tutelage to take copius notes of the professors’ lectures. Printing was a brand new profession and few books were available, even by the most noted theologians. So Ursinus’ lengthy lectures were written by his hearers, who often collaborated with each other to be as accurate as possible, and they were so valuable that they were saved. Later, they were compiled into book form and we have available to us the large tome called the Commentary on the Heidelberg Catechism. In its pages we find Ursinus’ responses to the numerous challenges and objections to the Catechism’s answers, and his own perspectives as he answers how the scriptures give direction for daily responses to many situations in the church, home or community. The brief Catechism is dwarfed by the Commentary, but it is quite inexpensive and there should be one in every Reformed church.

Learning the Catechism

A child learns to count with little blocks with numbers on them, and move on to higher forms of mathematics, algebra or calculus in later years. When the child becomes mature enough, someone takes the time to teach the youngster that there is a value to the numbers, with ascending quantities, and that they can be combined by addition, even subtracted, multiplied or divided. Without the first years there would have been no higher math, as it presupposes the earlier lessons of the elementary level.

In that same sense, learning the elements of the Christian faith builds upon the lessons of the earlier years, such as going to worship with parents and hearing them join the congregation in reciting the creed, learning the Commandments in Sunday church school, or praying in unison the same Lord’s Prayer at the community Thanksgiving Service — and all knew it! The lessons of the Catechism are not learned in a vacuum, but in the context of the student’s own history and experience. The learning process is also informed by previously learned ideas, such as in scripture readings, the words of hymns, bedtime prayers, and attendance at marriage or funeral rites, to name a few. It becomes obvious by the above that youngsters and adults alike can find the Catechism’s lessons easier to understand if they were exposed more frequently, even from infancy, with worship and learning experiences at home or in the church. It is also obvious, in a correlative way, that the more frequently the creeds, commandments and familiar prayers are used in worship and other settings, they introduce time and again the doctrines of the Christian faith and the necessity for personal commitment to Christ and his Church.

The Universal Faith

The Heidelberg Catechism is not the only one, as many were written before and since its first printing. But where many others pointed to the centrality of the Church or emphasized the individual’s role in the working out of salvation, the Reformation’s insistence on the centrality of Jesus Christ alone found its emphasis here. It is through him that the revelation of God was imparted, and in the time of the pre-Christian era as well as upon the arrival of Christ and his establishment of his holy Church. It is emphasized throughout by its dependency upon Holy Scripture for all of its answers.

By its reliance upon the Bible alone, the Catechism advances a universal perspective, taking into account the whole revelation of God from the patriarchs (Abraham, Moses, David) and the prophets (Isaiah, Ezekiel, up to the last, Malachi), but no less or more upon the four Evangelists, the Apostles and concluding with John’s Revelation. It reflects the history of all God’s people, the saints of all ages alike. And precisely because it is historical, the Lord speaking to all his Covenant people throughout the years, the truths of the faith are also ecumenical and catholic, universally true. The scriptural truth then rises above the days’ fads and local interpretations, requiring the Church to continually review its errant misconceptions and to always reform itself according to the faith once for all delivered to the saints.

For its 450 years, the Heidelberg Catechism has been a clearly stated and understood declaration for Reformed churches and a unifying instrument across boundaries and barriers of realms, language and culture. As it enables us to enter into conversation with the faithful of other centuries past, it is also a challenge to us to take seriously the whole company of God’s people past and present. Therefore, we are constrained to listen again to the voices of Zwingli, Luther, Calvin of yesteryear, but also the later voices of Bonhoeffer, Barth, Ravasz and Csiah. Yes, there are also the echoes of the suffering Church in Hungary, which in earlier and later years of torment under Muslin, Hapsburg or Communist tyrants clung to the Heidelberg Catechism’s beloved doctrines and until today finds in it its unity, strength and purpose. In this turbulent time we would do well to believe and profess the faith it proclaims today as at its writing by Ursinus.

Rev. Albert W. Kovacs

20 October AD 1012 Central Classis — Calvin Synod

Ligonier, Pennsylvania

.

Comments are closed for this Article !