In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Progressivism and Infallibility: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- 1800 Years of History Undone?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Onward to the Obvious: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Ultimate Interlocking Puzzle: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Augustine’s Six Day “Denial” (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Augustine’s Six Day “Denial” (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

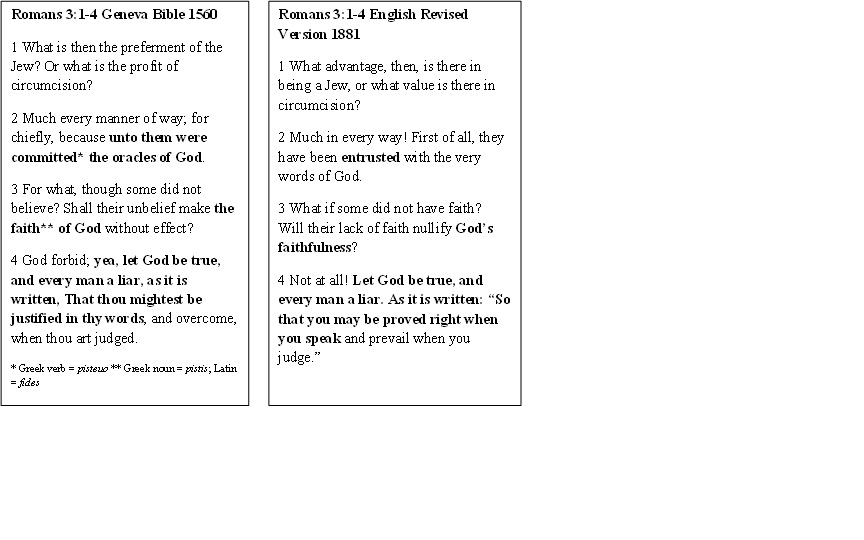

- The Faith of God: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Faith, Old English, and the Carpenter’s Apprentice: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Zwingli and the Kicker (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Zwingli and the Kicker (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Witness of the Law and the Other Sacrament (Part 1); “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Witness of the Law and the Other Sacrament (Part 2); “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- A Note to Follow “So”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The “La” Before “Foi” in Romans 12:6: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “‘Analogia’ and Paul the Wordsmith”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “The Hebrew Analogy”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Syrophoenician Analogy “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Did Ben Franklin Speak “According to the Analogia of the Faith”?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “In Me First”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Evil from the Hand of God?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- God’s Good Faith Promise Fulfilled: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The God Who Keeps Faith: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Cult of Mariolatry : “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Luther’s Characterization of James’ Epistle?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- A Plea for the Most Literal Rendering of the “Faith of Jesus” Genitives

- Progressive Religion at Oyster U: A Poetic Narrative “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Absent from Absolutes?: “Yes and No” – “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 – Geneva Bible

- Concerning Jonathan Edwards: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 – Geneva Bible

.

.

In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part I)

.

“Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?”

Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

“Is not the cross the basis of our salvation?” asked sister Luane.

“I would say rather,” answered Sister Hope, “that the cross is evidence of our salvation.”

“I don’t think I understand what you mean.”

Michael Phillips, Heathersleigh Homecoming [1]

.

The Gospel Blender

.

Paul’s gospel, no less than the entire New Testament, represents a perfect blending of historical redemption and historical revelation. The former categorizes the view of Anselm (1033-1109), a theologian and Archbishop of Canterbury, and the latter the view of Abelard (1079-1142), a canon of Notre Dame in Paris and author of Sic et Non–Yes and No. Ablelard’s stormy career did not end with the abrogation of his secret marriage to Heloise but culminated in condemnation at the hands of Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) at the Synod of Sens in 1141.

For Anselm, the death of the Incarnate Son in space and time was necessary to satisfy the wrathful justice of God directed toward sin, and (implicitly and expressly) toward sinful men. For Abelard, the incarnation and death of Christ demonstrated the supreme expression of the love of God thereby revealing God’s true nature, altering fallen men’s preconceived notion of God as a mean-spirited ogre, [2] and creating faith where it did not previously exist. While both Anselm and Abelard rejected the long-standing atonement concept of ransom paid to the devil, Abelard, with equal energy, “repudiated Anselm’s doctrine of satisfaction.” [3] The triumph of Anselm’s understanding of Christ’s atonement is reflected in the historic Protestant confessions and in the modern evangelical world.

As for the likelihood that Anselm’s view was previously unknown or unexpressed, William Hordern stated, “It would be strange indeed if the Bible taught the fundamentalist [4] or Anselmic doctrine and if for the first thousand years of Christianity no one recognized it.” [5] The Waldensians who had long since inhabited the southern French alps expressed doctrinal agreement with the sixteenth-century Reformers. [6] Calvin frequently appealed to the early church fathers to corroborate the apostolicity of the Reformation doctrine and to contrast it with what later followed with the Roman medieval defection.

The Scottish George MacDonald’s nineteenth-century repudiation of Calvinism clearly involved a rejection of Anselm’s doctrine of the cross in deference to Abelard. MacDonald, a former Congregational pastor, was the primary influence upon C. S. Lewis and significantly influenced such other notable authors as Oswald Chambers, Hannah Hunnard, and Hannah Whitehall Smith. Michael Phillips has not only republished the Scotsman’s works, but continues to spread the Abelardian “gospel” of George MacDonald through the genre of historical fiction.

.

The Tait Test

.

Dr. L. Gordon Tait, Mercer Professor of Religious Studies Emeritus at the College of Wooster and the first American to be made an Honorary Fellow of the University of Edinburgh, acknowledged that “a satisfaction theory of the atonement” “has enjoyed a long history in the church” but argued, “The word ‘satisfaction’ does not appear in the Bible, and nowhere does the Bible say that if certain conditions are met or a price is paid, only then will God love us.” [7] But even if Isaiah 53:11 [8] were to be ignored in establishing the doctrine of Atonement, the esteemed professor would surely not deny the doctrine of the Trinity on the ground that the word “Trinity” does not appear in the Bible. But what of his claim that “nowhere does the Bible say that if certain conditions are met or a price paid, only then will God love us”?

To the degree that God’s love exceeds his forgiveness and is the foundation for it, Tait’s characterization of Anselm’s “satisfaction theory” exceeds William Hordern’s comment that “the Anselmic views are always in danger of picturing Jesus as doing something to make God willing to forgive.” [9] Both scholars suggest to this writer that Anselm’s doctrine of satisfaction represents Jesus as something akin to a Mediator between God and men–the very position Scripture ascribes to him. [10] The problem is that such a proposition is represented by Dr. Tait as unbiblical and by Hordern as “dangerous”! As for the “danger” of holding such a proposition, to be sure, Stephen was stoned to death; the apostles were imprisoned and, with the exception of John, were ultimately put to death on that account; and Paul, before he himself was martyred, had catalogued, for the benefit of the church at Corinth, a list of dangers and hardships he personally had faced. [11] In Tait’s defense, it is, of course, tragic whenever a professing Christian distorts the gospel by denying the love of the Father. But is it more tragic than denying the concept of appeasement on the grounds that it implies anger on the part of God the Father? Or is it the theologian’s task to shield the Almighty from any insinuation of anger on his part? Such seems to have been the mindset of D. M. Baillie, T.W. Manson, James Stewart, C. H. Dodd and others who suggested that the concept of propitiation, the appeasement of an angry God, is a pagan idea unworthy of the God of the Bible. [12]

.

John Calvin’s Anger Management Seminar

.

While “anger management” theologians have continued to rail against Anselm, Trevin Wax, author of Counterfeit Gospels: Rediscovering the Good News in a World of False Hope, recently wrote:

The god who is truly scary is not the wrathful god of the Bible, but the god who closes his eyes to the evil of the world, shrugs his shoulders, and ignores it in the name of “love.” What kind of love is this? A god who is never angered at sin and who lets evil go unpunished is not worthy of worship. The problem isn’t that the judgmentless god is too loving; it’s that he is not loving enough. [13]

Perhaps sixteenth-century Protestant Reformer John Calvin can help us out of this conundrum. Like Abel, Calvin “died, but through his faith he is still speaking.” [14]

In reforming Geneva, Calvin embraced the major Abelardian tenet when, after quoting John 3:16, he stated, “We see how God’s love holds first place, as the highest cause or origin; how faith in Christ follows this as second and proximate cause.” But Calvin corrected the Abelardian downside when he underscored the importance of the word “appeasing.” For “. . in some ineffable way, God loved us and yet was angry toward us at the same time, until he became reconciled to us in Christ. This is the import of all the following statements” (at which point Calvin quoted 1 John 2:2; Colossians 1:19-20; 2 Corinthians 5:19; Ephesians 1:6; and Ephesians 2:15-16). [15] To be sure, the Father’s love– the focus of John 3:16 is ultimately governed and communicated by the Father’s sovereign election which, according to the Father’s design, occurs through, and in reference to, the Son whom he loves. [16]

But the Geneva Reformer asked,

How did God begin to embrace with his favor those whom he had loved before the creation of the world? Only in that he revealed his love when he was reconciled to us by Christ’s blood. God is the fountainhead of all righteousness. Hence man, so long as he remains a sinner, must consider him an enemy and a judge. Therefore, the beginning of love is righteousness, as Paul describes it: “For our sake he made him to be sin who had done no sin, so that we might become the righteousness of God” [II Cor. 5:21]. This means: we, who “by nature are sons of wrath” [Eph. 2:3. Cf. Vg.] and estranged from him by sin, have, by Christ’s sacrifice, acquired free justification in order to appease God But this distinction is also noted whenever Christ’s grace is joined to God’s love. From this it follows that Christ bestows on us something of what he has acquired. For otherwise it would not be fitting for this credit to be given to him as distinct from the Father, namely, that this grace is his and proceeds from him. . . .By his obedience, however, Christ truly acquired and merited grace for us with his Father. Many passages of Scripture surely and firmly attest this. I take it to be a commonplace that if Christ made satisfaction for our sins, if he paid the penalty owed by us, if he appeased God by his obedience–in short, if as a righteous man he suffered for unrighteous men–then he acquired salvation for us by his righteousness, which is tantamount to deserving it. [17]

.

Endnotes

.

[1]. P. 145 Heathersleigh Homecoming is the third volume of Michael Phillips’s historical fiction series The Secrets of Heathersleigh Hall in which the lead character may fairly be said to be the unseen but oft-quoted Scottish author George MacDonald whose fascinating but nevertheless heretical views emerge from various characters–in this case Sister Hope.

[2]. Gen. 3:1-5

[3]. A History of the Christian Church, p. 265.

[4]. Hordern used the term “fundamentalist” to identify the Protestant doctrine which the “Liberals” were contesting in the early twentieth-century.

[5]. Hordern, p. 203.

[6]. Walker. p. 387

[7]. The Piety of John Witherspoon, p. 60

[8]. “He shall see of the travail of his soul, and shall be satisfied: by his knowledge shall my righteous servant justify many: for he shall bear their iniquities.” (KJV)

[9]. A Layman’s Guide to Protestant Theology, p. 203

[10]. 1 Tim. 2:5

[11]. Acts 7:52-60; Acts 4:3; 5:18; 2 Corinthians 11:23-33

[12]. D. M. Baillie, God was in Christ, pp. 186-189

[13]. “Rejoicing in the Wrath: Why We Look Forward to Judgment Day,” Christianity Today, July/August 2012, p. 51

[14]. Heb. 11:4

[15]. John Calvin, The Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book II, Chapter XVII, Section 2

[16]. Matt. 11:25-27; Luke 23:39-43; Rom. 9:6-8, 24; Ephes. 1:4

[17]. Institutes, II, xvii, 2-3

.

Works Cited

.

Baillie, D. M. 1948. God Was in Christ: An Essay on Incarnation and Atonement. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Brand, David C. 1991. Profile of the Last Puritan: Jonathan Edwards, Self-Love, and the Dawn of the Beatific. American Academy of Religion Academy Series, edited by Susan Thistlewaite. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

Calvin, John. 1960. The Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed., John T. McNeill. 2 vols. The Library of Christian Classics. Vols. 21 & 22. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Edwards, Jonathan. 1879. The Works of Jonathan Edwards, A.M., rev. & ed., Edward Hickman, 2 vols. 12th edition. London: William Tegg & Co.

Geneva Bible. 1560. www.genevabible.org/Geneva.html

Hordern, William. 1955. A Layman’s Guide to Protestant Theology. New York: The MacMillen Company.

Horton, Walter Marshall. 1955, 1958. Christian Theology: An Ecumenical Approach. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers.

Phillips, Michael. 1998. The Secrets of Heathersleigh Hall. 4 vols. Minneapolis: Bethany House Publishers.

Tait, L. Gordon. 2001. The Piety of John Witherspoon. Louisville, Kentucky: Geneva Press.

Walker, Williston. [1918] 1952. A History of the Christian Church. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

.

About the Writer

David Clark Brand is a retired pastor and educator with missionary experience in Korea and Arizona. He and his wife reside in Ohio. They have four grown children and six grandchildren. With a B.A. in the Liberal Arts, an M. Div., and a Th.M. in Church History, Dave continues to enjoy study and writing. One of his books, a contextual study of the life and thought of Jonathan Edwards, was published by the American Academy of Religion via Scholars Press in Atlanta.

.

Comments are closed for this Article !