Zwingli and the Kicker (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Progressivism and Infallibility: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- 1800 Years of History Undone?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Onward to the Obvious: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Ultimate Interlocking Puzzle: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Augustine’s Six Day “Denial” (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Augustine’s Six Day “Denial” (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- In Fairness to Abelard and Deference to Anselm (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

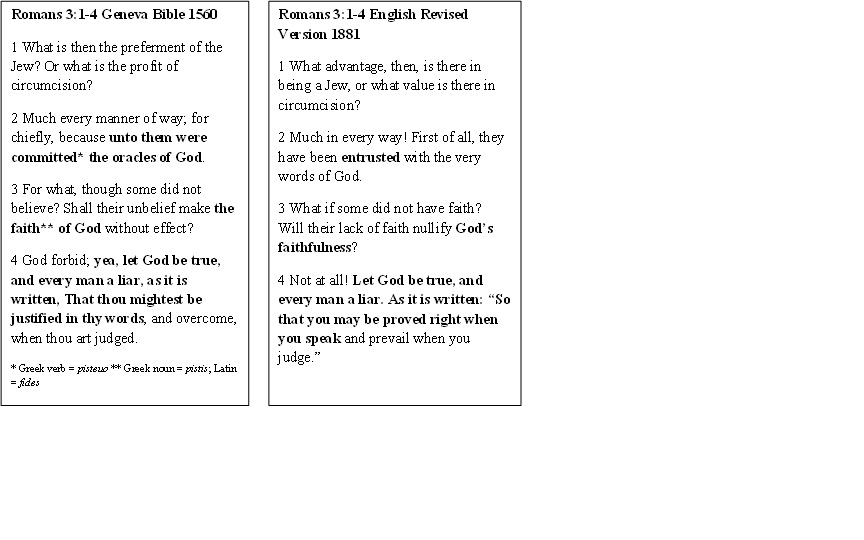

- The Faith of God: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Faith, Old English, and the Carpenter’s Apprentice: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Zwingli and the Kicker (Part I): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Zwingli and the Kicker (Part II): “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Witness of the Law and the Other Sacrament (Part 1); “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Witness of the Law and the Other Sacrament (Part 2); “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- A Note to Follow “So”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The “La” Before “Foi” in Romans 12:6: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “‘Analogia’ and Paul the Wordsmith”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “The Hebrew Analogy”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Syrophoenician Analogy “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Did Ben Franklin Speak “According to the Analogia of the Faith”?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- “In Me First”: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Evil from the Hand of God?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- God’s Good Faith Promise Fulfilled: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The God Who Keeps Faith: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- The Cult of Mariolatry : “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Luther’s Characterization of James’ Epistle?: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- A Plea for the Most Literal Rendering of the “Faith of Jesus” Genitives

- Progressive Religion at Oyster U: A Poetic Narrative “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

- Absent from Absolutes?: “Yes and No” – “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 – Geneva Bible

- Concerning Jonathan Edwards: “Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?” – Romans 3:3 – Geneva Bible

.

.

Zwingli and the Kicker (Part II):

“Shall their unbelief make the faith of God without effect?”

Romans 3:3 Geneva Bible

.

“Knowing that Christ being raised from the dead dieth no more; death hath no more dominion over him.” [1]

.

“I believe that Christ is truly in the Lord’s Supper,

nay, I do not believe it is the Lord’s Supper unless Christ is there.” [2]

.

Defining “Real Presence”

Consubstantiation [3] proved to be the “kicker” at the Marburg Colloquy of October 1529. After German Lutherans and Swiss Protestants had reached agreement on fourteen points of Christian doctrine, Martin Luther rejected Huldreich Zwingli’s offer of the right hand of fellowship. On the game-breaking fifteenth point concerning the Lord’s Supper, the German Reformer appealed to Christ’s words “This is my body” [4] over against Zwingli’s metaphorical understanding of those words. Church historian Kenneth Scott Latourette noted,

Zwingli was willing to concede that Christ is spiritually present in the Lord’s Supper and Luther granted that no matter what the nature of Christ’s presence only faith can make it of benefit to the Christian. Intercommunion might have been attained had not Melanchthon objected on the ground that for Luther to yield might make reconciliation with the Roman Catholics impossible. [5]

In his Exposition of the Christian Faith published prior to his death in 1531, Zwingli emphasized Christ’s spiritual presence in the Lord’s Supper, noting that the “is” of 1 Corinthians 11:24 should be understood in the sense of “signifies.” [6] In this regard, his view of the Lord’s Supper was closer to Calvin than many modern Calvinists realize. Calvin wrote,

Yet a serious wrong is done to the Holy Spirit, unless we believe that it is through his incomprehensible power that we come to partake of Christ’s flesh and blood. Indeed, if the power of the mystery as it is taught by us, and was known to the ancient church, had been esteemed as it deserves for the past four hundred years, it was more than enough to satisfy us. The gate would have been closed to many foul errors that gave rise to frightful dissensions which both then and in our time have plagued the church, while inquisitive men demand an exaggerated mode of presence, never set forth in Scripture. . . . For us the matter is spiritual because the secret power of the Spirit is the bond of our union with Christ. [7]

Dr. Clifford M. Drury, the late Professor of Church History at San Anselmo Presbyterian Seminary, characterized the distinction between Zwingli and Calvin as primarily one of emphasis noting that for Zwingli the bread and wine were representative of what was absent, whereas for Calvin the bread and the wine were representative of what was present. [8]

Deploying the Greek koinonia twice in 1 Corinthians 10:16, the apostle Paul focused on the significance of the communion associated with the partaking of the “bread” and, in turn, of the “cup of blessing.” Our understanding of that “communion” in the body and blood of Christ, however, is critical, and must be informed by Paul’s use of the same Greek koinonia in the benediction of 2 Corinthians 13:14. For in that passage Paul identified “communion” or “fellowship” as the unique blessing bestowed by the Holy Spirit. “Communion,” accordingly, is spiritual in essence being established by the Third Person of the Godhead who applies the finished work of Christ to the believer. [9] Because the ancient Jewish and Roman worlds were alienated from the living God, [10] and hence did not grasp this spiritual partaking of Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper; [11] they accused the early Christians of cannibalism. [12]

“Is” and the Biblical Metaphoric

With reference to Christ’s words, “This is my body,” Zwingli set forth the following examples from Scripture to illustrate that verbs of “being” are frequently used metaphorically:

• Gen. 41:26: “the seven beautiful kine, and the seven full ears, are seven years of plenty.”

• Luke 8:11: “The seed is the word of God.”

• Matt. 13:38: “The field is the world.”

• John 10:9: “I am the door.”

• John 15:5: “I am the vine.”

• John 8:12: “I am the light.” [13]

To be consistent in their literalism, Roman Catholics should insist on the literal meaning of “bread” in 1 Corinthians 10:16 and 1 Corinthians 11:26. To do so, however, only accentuates the point that it is just that– “bread” that is literally partaken however with great spiritual/metaphorical significance. The “cup” obviously is not to be partaken literally, but being a metonym [14] in this instance, it represents what is contained in it, namely the fruit of the vine which, in turn, signifies Christ’s blood.

Accordingly, beginning with the Swiss, the Reformers dispensed with the Roman practice of kneeling at the table of the Lord’s Supper lest worshipers lapse into the idolatrous error of adoration of the host (those symbols associated with Christ’s body and blood). For Christ did not command concerning the bread, “Take, worship,” but rather “Take, eat.” For Reformed Protestants in Switzerland, France, The Netherlands, and Scotland, the table of the Lord’s Supper was never considered an altar. [15] Since Christ had offered up himself “once for all” on behalf of sinners and had risen from the dead, he could never die again. [16] Drury noted that Zwingli was the first to stand behind the table of the Lord’s Supper and face the people.

The Deception of Pressing the Literal

Zwingli noted that when Christ first administered the Supper, he had a mortal body. If the original disciples, therefore, had partaken literally of Christ’s body, they would have partaken of what was mortal. Those who partook subsequent to Christ’s resurrection and ascension, however, if they literally partook of Christ’s physical body, would have partaken of an immortal body. [17] Pressing the literal meaning of “is” in Christ’s words in 1 Corinthians 11:24, accordingly, poses serious exegetical problems taking the literalists far away from the straightforward meaning of the institution of the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:17-32.

Scripture neither directs us to the ubiquity of Christ’s body nor to the ex opere operato alteration of physical substance, the “miracle of the mass” pronounced by the Roman Catholic Church. Nor should Jesus’ teaching in the aftermath of the multiplication of loaves in the feeding of the five thousand be used as a pretext in that regard. [18] Clearly the “eating” and “drinking” to which Jesus calls sinners in John 6:56 corresponds to the appropriation of the new covenant benefits of Christ “through faith in his blood” mentioned in Romans 3:25. Peter reminded Christian believers that they were made “partakers of the divine nature” [19] –a nature revealed supremely, spatially, and publicly on a Roman cross; and this best captures the significance of Christ’s words in John 6:56.

The truth that believing in the Son is the “work of God” is a major theme of John chapter 6, and it coheres with the force of the Greek “faith” genitives of Romans chapter 3. [20] The large body of Jews whom Jesus addressed in John chapter 6 simply did not grasp the meaning of eating the flesh of the Son of God, or drinking his blood, because they did not have the “faith of God.” [21]

So has been the case with many thousands of professors of the Judaeo- Christian religion to the present time. The Roman Catholic Church’s linking of salvation to the ex opere operato “miracle of the mass” encroaches upon the office of the One who, “when he had by himself purged our sins, sat down on the right hand of the Majesty on high.” [22] That issue was front and center during the Protestant Reformation.

Jonathan Edwards describes the corruption resulting from compounding truth with error:

. . . the lying miracles of the papists, may for the present beget in the minds of the ignorant, deluded people, a strong persuasion of the truth of many things declared in the New Testament. Thus when the images of Christ, in popish churches, are on some extraordinary occasions, made by priestcraft to appear to the people as if they wept, and shed fresh blood, and moved, and uttered such and such words; the people may be verily persuaded that it is a miracle wrought by Christ himself; and from thence may be confident there is a Christ, and that what they are told of his death and sufferings, resurrection and ascension, and present government of the world, is true; for they may look upon this miracle, as a certain evidence of all these things, and a kind of ocular demonstration of them. This may be the influence of these lying wonders for the present; though the general tendency of them is not to convince that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, but finally to promote atheism. Even the intercourse which Satan has with witches, and their often experiencing his immediate power, has a tendency to convince them of the truth of some of the doctrines of religion; particularly the reality of an invisible world, or world of spirits, contrary to the doctrine of the Sadducees. The general tendency of Satan’s influences is delusion; but yet he may mix some truth with his lies, that his lies may not so easily be discovered. [23]

“Shall their unbelief make the faith of God of none effect? God forbid: yea, let God be true, but every man a liar.” [24]

.

Endnotes

[1]. Rom. 6:9

[2]. Huldreich Zwingli, Exposition of the Christian Faith, On Providence and other essays, p. 285

[3]. Luther’s doctrine of consubstantiation was related to his doctrine of the ubiquity of Christ’s body based upon the union of Christ’s divine and human properties, not strictly physical presence, but nonetheless real presence, whereby Christ is with, around, through, above, and under the bread in the Lord’s Supper, and likewise with respect to the wine. By contrast, transubstantiation, recognized as an official doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church in 1000 A.D., represented the miraculous physical alteration of the substance of the bread and the wine into the literal body and blood of Christ at the point of consecration of the elements by the officiating priest. Thereby (1) the table of Lord’s Supper became an altar; (2) kneeling before that altar became an act of recognizing Christ’s physical presence; and (3) wine no longer would be given to the people out of fear that it would be spilled. Luther, on the other hand, held that if a piece of communion bread or a drop of consecrated wine were to fall to the floor and a mouse ate or drank it, the mouse would be eating bread or drinking wine and nothing more. For Luther, faith in Christ was essential to the eating of Christ’s body, but there could be no faith, and hence no sacramental eating, apart from the Word of the Gospel. On the basis of Acts 1:11 and other passages, Zwingli did not believe that Christ’s physical human body, even in its glorified state, could be at two places at the same time.

[4]. 1 Cor. 11:24

[5]. A History of Christianity, p. 726

[6]. See Chapter IV: “The Presence of Christ in the Supper,” and Chapter V: “The Virtue of the Sacraments” in Zwingli’s Exposition of the Christian Faith, in the volume On Providence and other Essays, pp. 248-260.

[7]. Institutes of the Christian Religion, IV, xvii, 33

[8].Notes from Professor Drury’s class on Presbyterian History and Church Polity conducted at Fuller Theological Seminary in 1967.

[9].John 16:14-15; 1 John 5:6-8

[10]. John 8:42-44; Ephes. 2:1-3

[11]. John 6:60-63; 1 Cor. 2:12-14

[12]. Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church, p. 49

[13]. Zwingli, On True and False Religion, pp. 224-227

[14]. Merriam Webster defines “metonymy” as “a figure of speech consisting of the use of the name of one thing for that of another of which it is an attribute or with which it is associated (as “crown” in “lands belonging to the crown”).”

[15]. Professor Drury underscored these Reformation principles.

[16]. Heb. 9:25-10:10.

[17]. Zwingli, On Providence and other essays, pp. 255-256

[18]. John 6:26-64

[19].2 Pet. 1:4)

[20]. John 6:28-29; Rom. 3:3, 22, 26

[21]. Rom. 3:3

[22].Heb. 1:3; 1 Tim. 2:5

[23]. Jonathan Edwards, Treatise on Religious Affections, Works, 1:294

[24]. Rom. 3:3

Sources

Calvin, John. 1960. The Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed., John T. McNeill. 2 vols. The Library of Christian Classics. Vols. 21 & 22. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press.

Drury, Clifford M. 1967. Class on Presbyterian History and Polity. Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, CA.

Catechism of the Catholic Church: With Modifications from the Edito Typica. 1995. New York: Doubleday.

Edwards, Jonathan. 1879. The Works of Jonathan Edwards, A.M., rev. & ed., Edward Hickman, 2 vols. 12th edition. London: William Tegg & Co.

Geneva Bible. 1560. www.genevabible.org/Geneva.html

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. 1953. A History of Christianity. New York; Harper & Row Publishers.

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. Tenth Edition. 1994. Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster, Incorporated.

The Holy Bible. 1611 Edition. King James Version. New York: Thomas Nelson Publishers.

Walker, Williston. [1918] 1952. A History of the Christian Church. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Zwingli, Huldreich. [1929] 1981. Commentary on True and False Religion. American Society of Church History Reprint. Labyrinth Press, Durham, North Carolina

——–. On Providence and other essays. [1922]. 1983. Edited for Samuel Macauley Jackson by W. J. Hinke, ed. American society of Church History. Reprint. Labyrinth Press: Durham, North Carolina.

About the Writer

David Clark Brand is a retired pastor and educator with missionary

experience in Korea and Arizona. He and his wife reside in Ohio. They have

four grown children and six grandchildren. With a B.A. in the Liberal Arts, an

M. Div., and a Th.M. in Church History, Dave continues to enjoy study and

writing. One of his books, a contextual study of the life and thought of Jonathan

Edwards, was published by the American Academy of Religion via Scholars

Press in Atlanta.

Comments are closed for this Article !